I wanted to go over some basics of building a profitable trading system by looking at “pot odds” a term applied in the game of poker and “expected value” and how it is interchangeable to trading. I am usually not a fan of looking at expected value because it doesn’t properly frame in the potential for massive account volatility, but it is still useful in understanding the basic requirements for a profitable system and can assist people new to trading or who have not yet learned to be profitable why they might have some “leaks in their game”. “pot odds” looks at the amount you can win, vs the amount you have at risk to determine the necessary probability of your decision in order to be profitable. From it you can also determine “expected value (EV) per hand (or per trade) ASSUMING the same amount risked every time.

In other words, say your opponent moved all in for the size of the pot on the flop. You get paid 2:1 to call since you must match your opponents bet, but get twice that (the pot AND the opponent’s stack) if you are right. You can then lose twice, win on the third and win everything you lost back. Therefore, you need only just better than a 1 out of 3 chance of winning for the call to be “profitable” in the long run.

If you have your entire bankroll at risk rather than a small percentage you are overextended and it is not a long term profitable decision because it will inhibit your ability to earn in the future as you will not be able to recover from a loss. “bankroll management” as it is called in poker and “position sizing” as it is called in stock trading is an important seperate topic that combined with “pot odds” greatly influences your long term profitability.

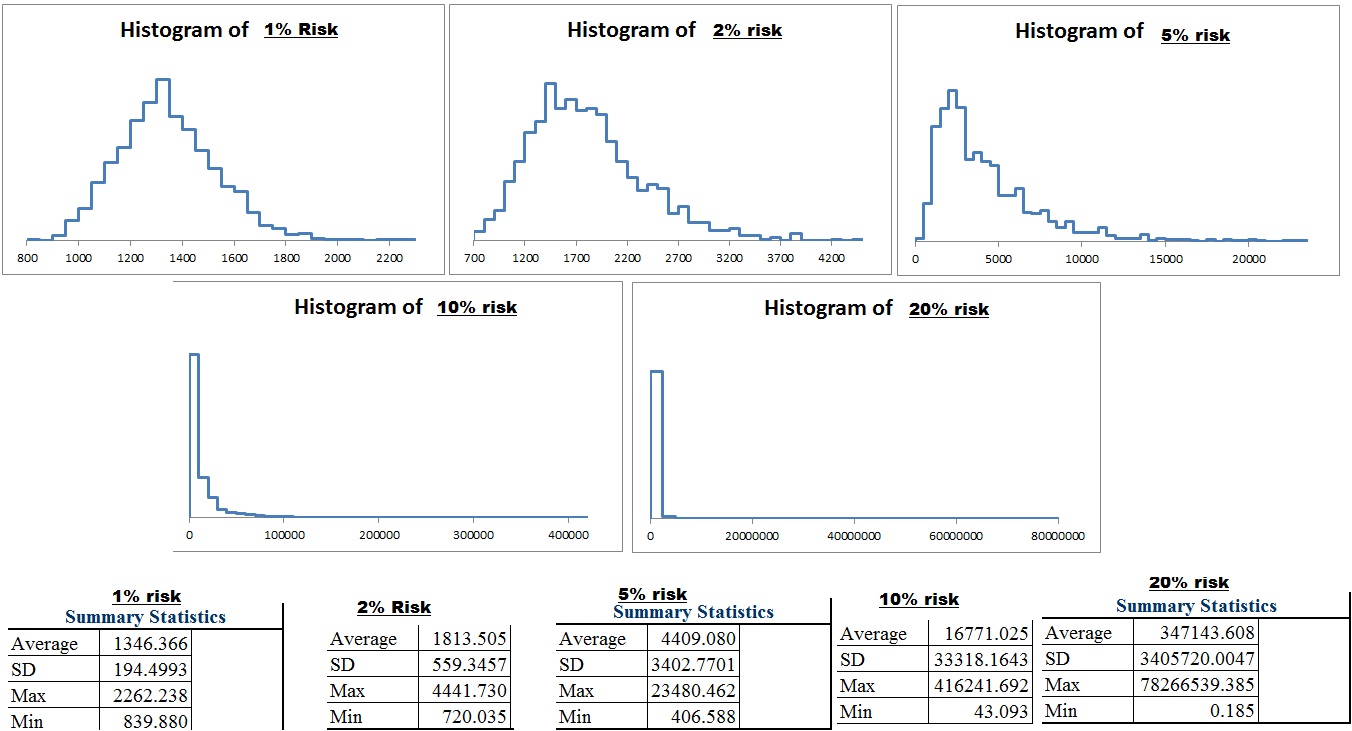

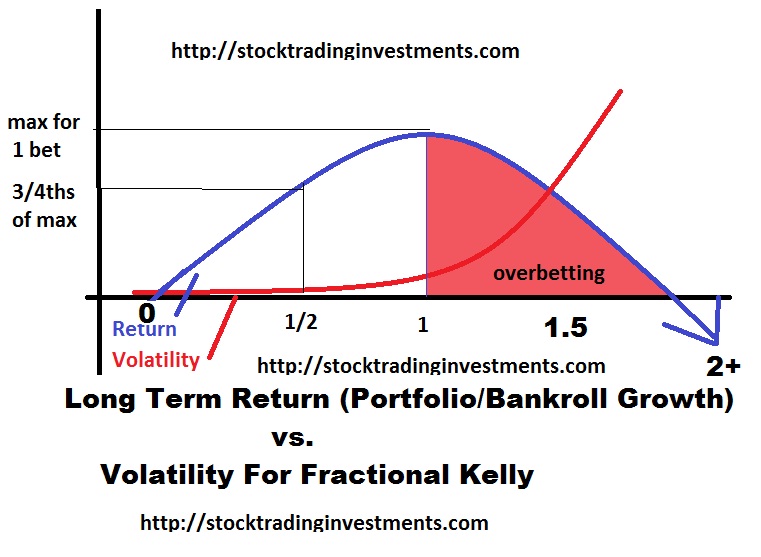

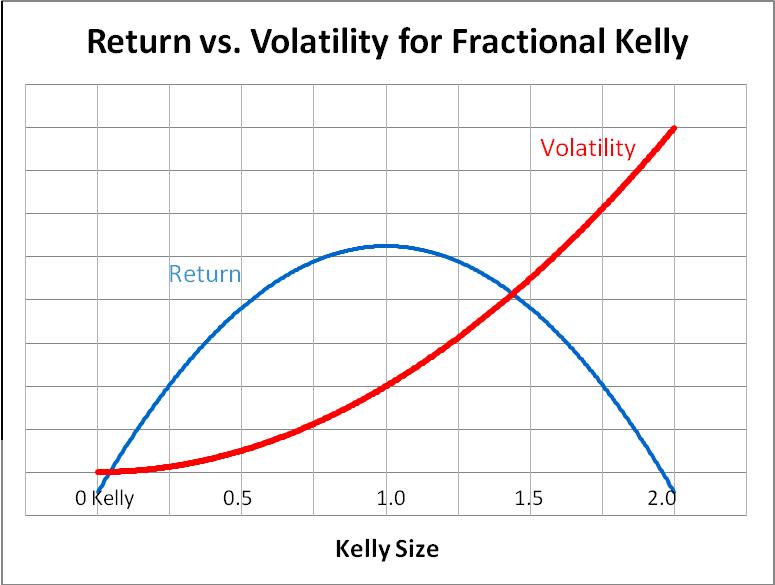

What novice poker players in cash games and traders often ignore is the fact that they will lose due to volatility. Lose 10% of capital, you need 11% just to get back to even, so 1% is lost due to volatility (it is actually less since multiple gains will also compound at a less substantial rate). Lose 50% of your capital and you need 100% return to get back to even.

betting more than 2 times the “full kelly” actually turns a profitable strategy unprofitable over ANY time frame, and erases any skill edge you have. While your winners may also compound, your losses create disproportionately large drawdowns that require a greater skill or edge to overcome to get back to even, and due to simple chance those drawdowns are certain to occur over a long enough time horizon with a correlated, unhedged system. Your edge is not as profitable as the expected value calculation in reality, at least not without introducing a “risk of ruin”. But I digress, let’s keep things simple… Pot odds. To keep things simple and ignore “uncertainty”, I want to use a situation in trading which the numbers tend to be a bit more concrete as opposed to uncertainty, so I want to give the example of “risk arbitrage” through buying into mergers and acquisitions.

betting more than 2 times the “full kelly” actually turns a profitable strategy unprofitable over ANY time frame, and erases any skill edge you have. While your winners may also compound, your losses create disproportionately large drawdowns that require a greater skill or edge to overcome to get back to even, and due to simple chance those drawdowns are certain to occur over a long enough time horizon with a correlated, unhedged system. Your edge is not as profitable as the expected value calculation in reality, at least not without introducing a “risk of ruin”. But I digress, let’s keep things simple… Pot odds. To keep things simple and ignore “uncertainty”, I want to use a situation in trading which the numbers tend to be a bit more concrete as opposed to uncertainty, so I want to give the example of “risk arbitrage” through buying into mergers and acquisitions.

According to this blog entry, 97 deals were completed, only 2 deals failed. However, many others remain unresolved and sometimes it may take longer than anticipated to close which doesn’t eat into your total profits for the trade, but does eat into your annualized profits since it takes longer for you to be able to reuse that capital. Since we are concerned in this article about profitability and pot odds, time will not be factored in. Even though almost 98% of deals closed, we will leave a bit more margin of error since some deals can linger on for years and then not close which could skew the numbers a bit. To be safe, we will say over 90% of deals go through and we can say that with pretty substantial confidence. At 90% chance of being right to win X and 10% chance to be wrong and lose 100% we must solve for X such that -.9x=-1*.10 or.9x=-.1 or -.1/-.9=1/9=.111111=11.1111%.

If you would lose 100% and win 11.111111% when you are right, the strategy of buying into these deals post announcement would be break even. So if you put your entire capital at risk, you would have the “pot odds” to buy any time there is a 11.11% payout or better. But when deals fail, they don’t go to zero, they drop down to around their pre-buyout price on average. This can change from deal to deal and some deals may just be in a constant downtrend.

If you had a downside of only 10% and an upside of only 5%, how would it compare with a trade with a downside of 100% and upside of 20%? You can confirm the expected value by downside of a loss (expressed as negative percentage) times probability of a loss plus upside of gain plus probability of a gain.

System 1 10% downside, 5% upside:

(-.1*.1)+(.05*.9)=.035=3.5% per completed deal.

(-.1*.1)+(.2*.9)=.08 or 8% per completed deal.

This shows why I don’t like expected value in comparing two systems, you risk insolvency by putting 100% of your capital into the trade with the “higher expected value” where as you only put 10% of your account at risk with the “lower expected value trade” If you were to risk 10% of capital on the 2nd strategy, you would only grow your portfolio by 0.80% per deal. As such the deal providing the better risk reward assuming equal probabilities of success/failure is almost always going to provide the better return on risk. You must evaluate system on an equal portfolio risk basis to truely determine which is better. The kelly criterion is a good metric for comparing one system to another on an equal risk basis. However, the kelly criterion should not be used for position sizing as it is probably 5 times more aggressive than it should be (or more) due to the false assumptions the formula makes about having an “infinite time frame”, a “certain, predefined known edge” and “complete emotional tolerance for all volatility that does not effect your edge” and that multiple bets at a lower percentage with a low correlation provides a better return on risk overall.

Additionally, if you could complete 12 trades a year in the 3.5% expected value system and the 8% per deal system took over a year, it would be much more profitable, so a raw calculation of “expected value per trade” must first be “normalized” (in this case normalized means something very different than “normalizing” volatility” as instead it means it should be set up to reflect the “normalized rate of return at a given level of risk” to reflect overall growth on portfolio given equal risk via position sizing). Then it must be also “annualized” so that they are equalized on a particular time frame after fees… However, due to uncertainty, you also must consider that the large edge that compounds fewer times is less vulnerable to small changes that may negatively impact the ROI more than you thought.

I don’t want to get any more complicated than I already have in this article, but for now I will tell you to practice by looking at your “risk” and your “reward” and measuring out your probabilities required to break even. For example if you have a target price that nets 3 times your risk, you need to hit your target 1/4 times in order to break even. With options if you try to hit around “break even” on hitting your targets or even lower, the trades that expire in the money and have to be sold for a slight gain, break even and only a slight loss as opposed to the entire risk of the option PLUS the occasional trade that runs beyond the target will create profitability in the system. I get into more specific and more realistic trading systems in part 2 and part 3.

Comments »