Capital has to move. I believe the market can almost never be in a state of equilibrium because new debt is being created which creates additional capital that changes the balance of allocation, and old debt is being replaced when it’s being paid or assets are being foreclosed for the inability to pay and moey leaves the system or rotates away from one particular system such as a domestic, localized economy to a foreign one.

As such, the efficient market hypothesis can almost never be exactly correct, and if it could be, it only is for a moment since new debt being created and old debt coming due and interest payments are never coordinated to sustain parody in the market place. People have to make moey to pay bills and transactions HAVE to occur. If they don’t, such as in communism, the economy collapses as has occurred historically anytime any nation even attempts to move towards a communistic state.

With this in mind, we still should care about how one might position in an effecient market, because a true “game theoretic optimal solution” or “equilibrium solution” is indifferent to how the actual market is positioned. The key behind this philosophy is to position such that you profit from a movement of capital regardless of in which way it occurs.

A simplified example is shown at the top of this post, but an even more simple one would be a world where you could choose between 2 types of currency assuming neither could be eliminated from legal usage. The optimal “equilibrium” solution would be 50% of each at all times. If 99.9% of the world used dollars, you still would gain from 50% mixture of each because you’d maintain the ability to reduce higher and add lower. If it was 99% the other way that would also be the case. Although a more “exploitative” solution would be to position the inverse of the crowd such as being 99.9% of the currency that is owned by .1% of the population, that doesn’t detract from the profitability of the “equilibrium” solution of 50/50%

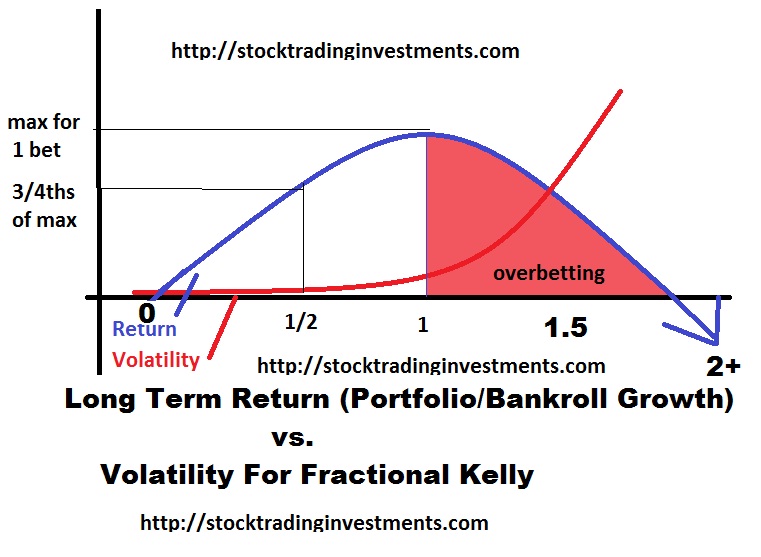

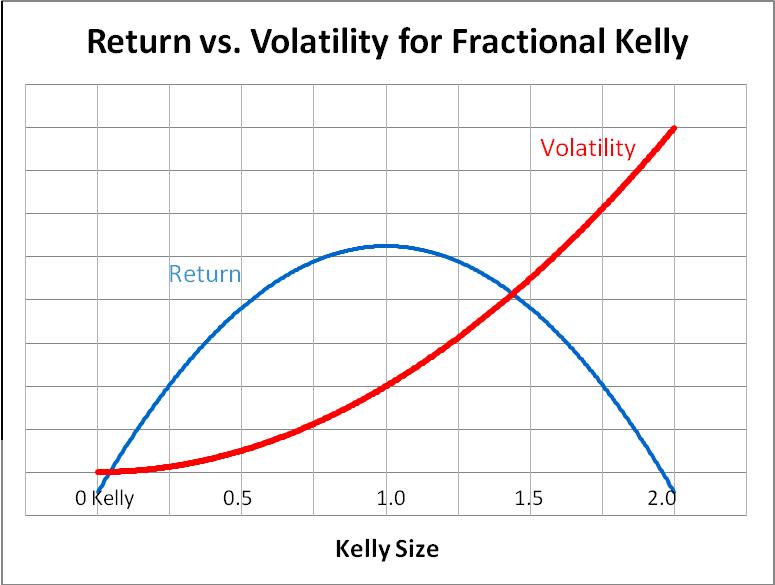

Understand this difference because I do not advocate an “equilibrium strategy” entirely, but by being aware of it you can deviate from it to the degree by which you have an edge and to the degree by which you can stand volatility.

If you have an edge, you can try to assess that edge probabilistically and use simulations to match your goals such that you have an expectation that satisfies you at a level of volatility that you can stand.

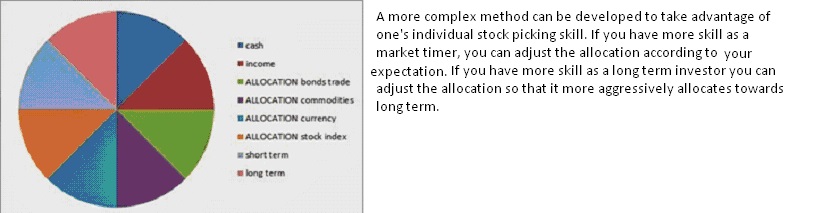

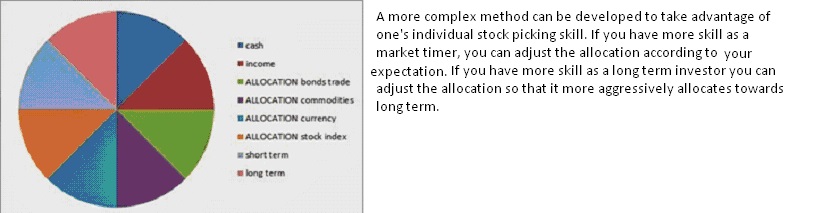

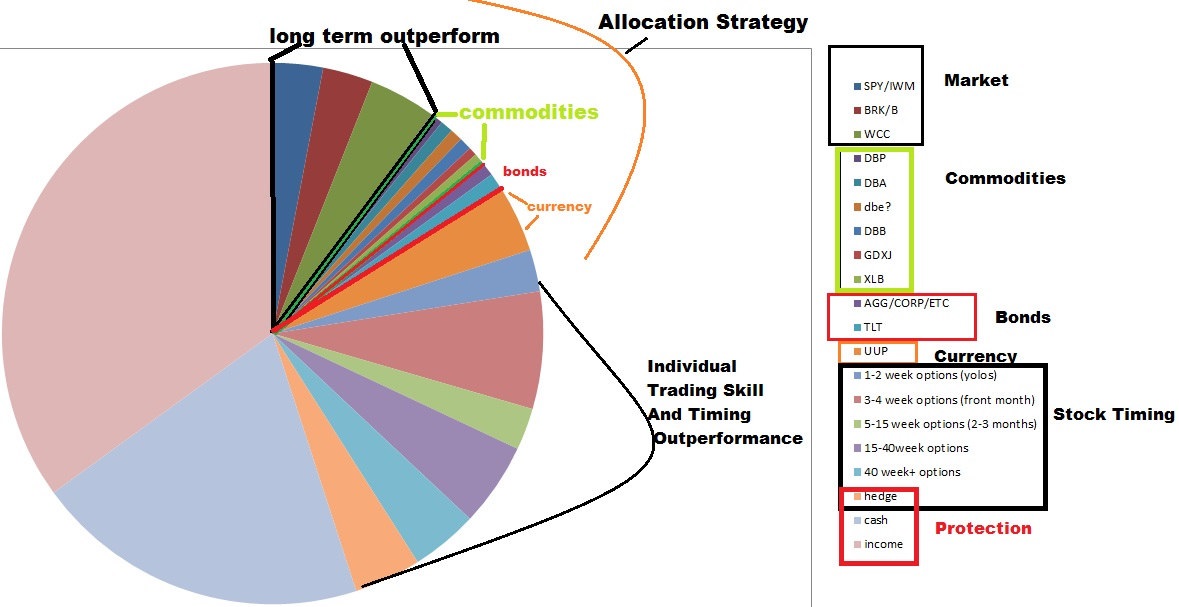

If you were to integrate your ability to make short and long term trades, you might create a baseline that adds in an edge playing the market, but curbs it with an allocation based equilibrium strategy as a core staple of that strategy in the following regard.

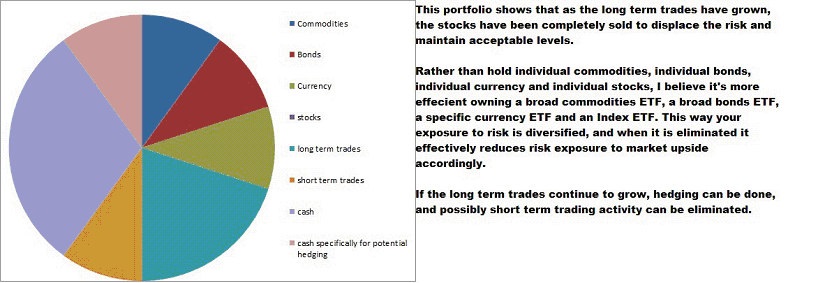

As you can see, by including individual short term and long term trades as an allocation, there is a bias towards stocks and stock picking.

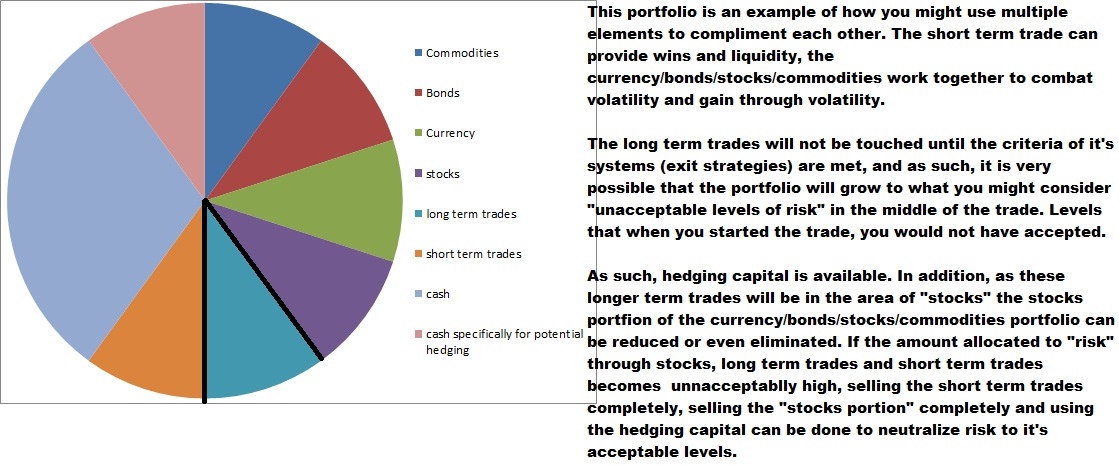

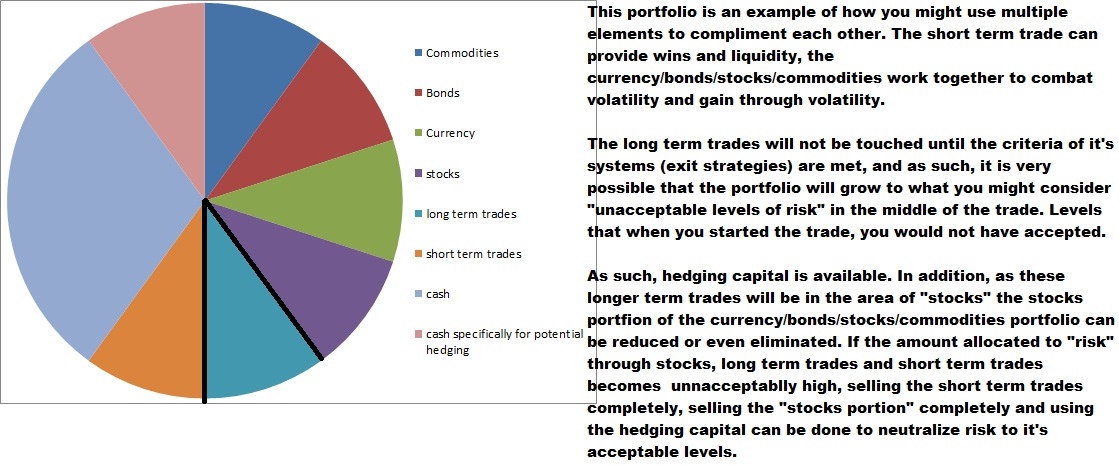

With the introduction of this, the problem is that over time your allocations will change and the reality of transaction fees require less frequent rebalancing. Also, individual trades usually have upside expectations and you want to let your winners run. As such it is possible that your individual positions may cause portfolio to grow out of balance. So you probably want to build in a more flexible mechanism to maintain overall parody with regards to your intended allocation of risk and stocks overall. This can be demonstrated below

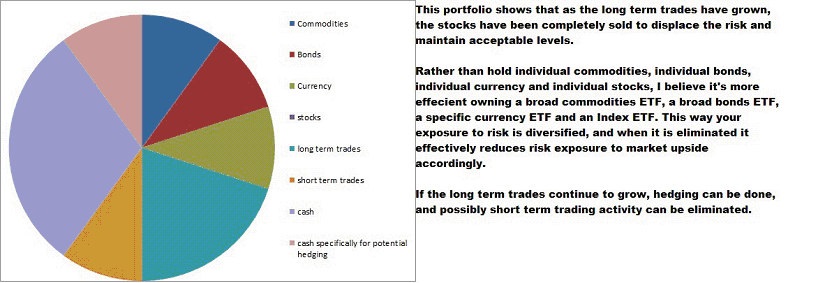

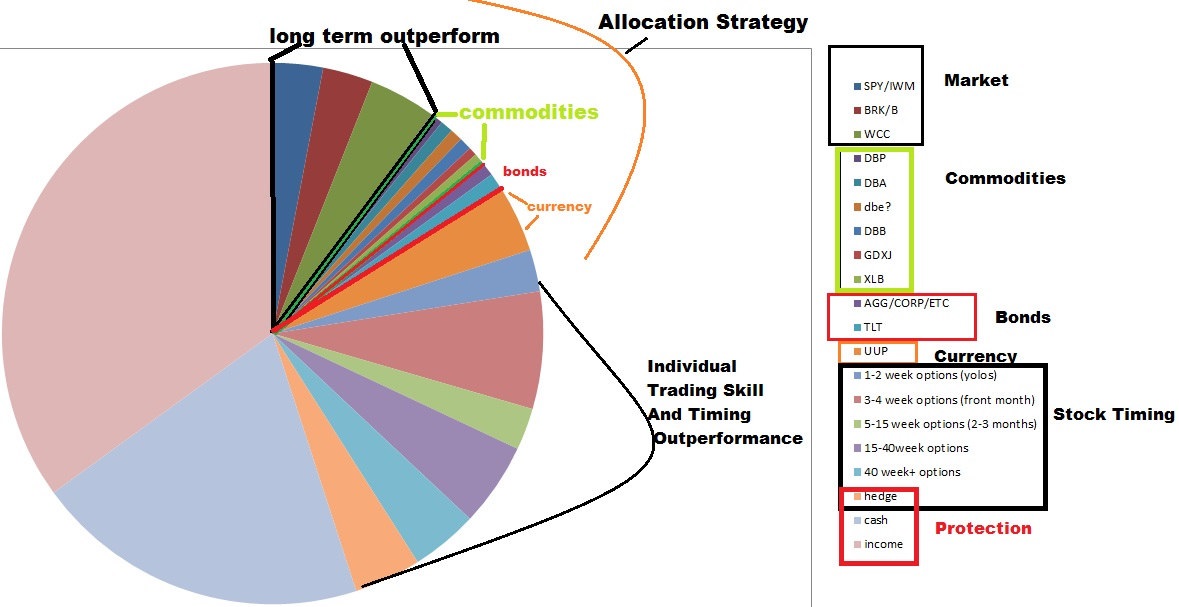

Rather than sell short of targets to maintain balance in asset allocation, you can use this reflexive, adaptive model to maintain the balance. As long term allocation grows you can reduce or entirely sell your broadbased stock ETFs. As short term allocation grows you can add hedges that last at least until your exit strategy triggers a sell and the increase in cash can allow you to make the adjustment to bring your strategy back into the intended risk allocations. You can develop more complex models to work subasset class allocations as well, and even try to handicap those or handicap the actual market movements by weighting your positioning according to risk and reward and expectations overall to more aggressively try to game the market as well as use leverage.

If you believe that you have a large enough edge and want to use additional information, you may use volatility as a tool and include options.

When volatility is high, you add to option selling strategies or XIV or SVXY ownership, and you might add to broadbased ETFs since correlation tends to be higher and the edge for picking stocks is less. You might increase longer term exposure following a crash weighting heavier in value and fundamentals. When volatility is low, you add to overall option exposure and may opt to reduce your allocation of XIV or SVXY. When correlations are less you may want to increase option ownership and decrease broadbased ETF ownership and look to apply your “edge seeking” as a larger percentage of your allocation.

This dynamic approach can still have with it a set of rules from which to govern the overall intent, and some kind of checklist to help you operate it efficiently as intended. The overall idea is to not get emotional and allocate emotionally, but instead strategically according to a plan made when your mind is operating at a high level, rather than when you are in fight or flight mode and you’re in “panic mode” and your amygdala is active.

So if I were trying to game the market right now, on the long term I may be interested in commodities, but in the short term I don’t see any setups. Any allocation towards ETFs or calls would have to be with plans of long term ownership. I think it’s a good entry for a longer term horizon on the stock market, but the individual names aren’t suppolying great entries aside from maybe some long term stock investments.

So with a volatility spike I’m rotating out of my individual stock trades as they stop out, and then if I have any hedges, I’m seriously reducing or taking them off as the decline reaches extreme. I’m looking on adding or increasing an inverse volatility ETF as long as the primary bull market thesis remains intact, and I’m looking to position for long term stocks but I’m not really looking to add long option strategies. I may be willing to sell puts on stocks I’m willing to buy or sell put spreads on stocks with high IV that look to be likely to hold or go higher.

You don’t necessarily need to force trades, but if you have thought all of this out and have thought out position size, maximum and minimum allocation for each assetclass or a way to objectively determine the allocation based upon certain measures, you will avoid fear taking over.

You will also be able to remain consistent. One of the biggest problems traders run into is that at the bottom, an allocation of 50% stocks seems high, where as at the top it seems low… At the bottom finding individual stocks to buy is tough, where as at the top they are easy. This is why you need a system in place while you’re thinking rationally that you can apply as the market changes, or at least increase the size of your hedges and bearish bets at the “top” while selling you broadbased ETFs to counterbalance your ability to have confidence with individual positions without unnecessarily over exposing yourself.

You also need to have thresholds at which you rebalance. Perhaps if a stock is within 5% of targeted allocation you don’t bother rebalancing, but outside of that number you do.

from an exploitative philosophy it’s okay to increase your allocation as the market goes lower if you are buying individual stocks, and you have some sort of risk management mechanism which acts as a kill switch if buying lower fails. While in equilibrium strategy you don’t want to expose yourself to further declines with a “martingale” type of strategy, there are many times when both the odds of a bounce and the expectation when it does happen actually increases as stocks get more oversold. But you need to have limits. So if your average allocation of an asset class is 25% you might take that up to a maximum of 40% when buying the ideal oversold conditions and down to 10% or 5% when selling oversold.

I can’t define these to you because that depends upon what your pain tolerance is and what your goals are and timeframe for those goals, and whether or not that is realistic for you.

With an equilibrium strategy, you are basically looking at a strategy that works over an infinite time horizon, where as realistically you should approach it with variance in mind. As such, position sizing becomes important and your cash position should increase. This is why the logic to weighting assets by volatility may actually make some sense on the surface, but I don’t believe it’s pure equilibrium strategy.

Unfortunately, that which is not volatile may not remain that way forever. I believe real estate had not undergone much downside volatility at all for decades until it finally crashed in 2007-2009. The global demand for bonds on the basis that it has been “safe” or less volatile isn’t an accurate reflection of the last 200 years of history where governments defaulted, nations have risen and fallen and political power and influence has shifted. It may provide some normalization of risk through the INCOME, but that doesn’t make it immune from default risk or loss of confidence and asset class wide loss of risk appetite. Since that risk still exists, you have to ask yourself if the prospect of complete default is worth such a low yield. For example, a 2% yield requires 36 years of interest accumulation until it makes a 100% return. If the chances of a default in that time period is greater than 50% than there is no advantage at all from holding bonds instead of just cash. In fact, it’s worse to hold bonds probably even if those odds were 40% because of volatility risk, opportunity costs of not being invested elsewhere, taxes on income and “black swan” risk even though there are some advantages in curbing volatility as a result of income. For many people even if that amount were 20% due to risk tolerance and transaction costs it may be better to hold cash than bonds, and even if it were much lower it’s not a huge loss. In some cases bonds can be used as collateral to borrow from to create leverage.

The real risk to cash is not the failure to return value, but the failure to protect purchasing power. As such, assets that gain from inflationary pressures, particular that effect the individual the most (such as food and fuel and stocks) is the best way to mitigate that risk. Currently, I don’t view a shift of capital from stocks to bonds as a major risk to stocks, so overall the exploitative strategy should probably be to have a mixture of cash stocks, some commodities and perhaps even betting against bonds and finding other income strategies such as preferred shares, corporate debt and occasional option selling strategies when conditions warrant it.

update:

Another approach to maximizing a particular expectation of return is looking at synergy between asset classes. Since the rotation of one into the rotation of another produces gains to the degree at which you are able to effectively buy low and sell high and since allocation of income provides additional capital to more efficiently rebalance and normalize returns, you can look at the downside deviation or the overall deviation of results to compare the overall portfolio strategy as a measurement of risk.

While this only tells you a backwards looking result of how volatility can be smoothed, it is more appropriate than backtesting of actual results since it’s looking at historical correlation.

I came up with the following strategy as an effective means historically to balance risk efficiently as can be seen at this link.

Sortino ratio: 3.23

Sharpe ratio: .87

CAGR: 10.23%

Std Deviation: 8.08%

worst year -2.71%

Backtested since 1985

Allocation:

Intermediate term treasuries 29% (IEF)

Long term treasuries 41% (TLT)

Small Cap Value 11% (IWN)

Mid Cap Value 14%

Large Cap Growth 5%

Midcap values weren’t around before 1985 so the following is the best I could do backtested since 1972.

Sortino Ratio 2.21

Sharpe ratio .76

CAGR 9.81%

std deviation 6.18

worst year -1.67%

10% Small Cap Value

12% Int Small Cap

70% Intermediate term treasuries

8% gold

Another strategy which involves cash to reduce the volatility is

8% small cap value

11% int small cap

3% LT treasuries

47% intermediate term treasuries

24% cash/money market

7% gold

If you progress towards using leverage and rebalancing more frequently, you are going to have to increase cash position and income positions to replenish that cash position so you can normalize the volatility without having to pay a lot of extra transaction costs to rebalance.

Since the goal is not return overall but instead return vs downside volatility, you potentially could leverage this up significantly and still have less volatility than a non leveraged strategy that was more aggressively allocated. The result can be a better return on better risk.

I believe this philosophy is somewhat flawed since it looks at past performance and past risk as defined by volatility and past correlation to determine overall portfolio volatility. I think to some degree, the less volatility a market has experienced over the past the more vulnerable it is to more dramatic volatility if people are following models expecting the future to resemble the past. Once it starts producing more volatility than expected, that forces people to re-calibrate their models and reduce allocation which creates more selling pressure and more re-calibration among mutual fund managers and others.

But I think you can still look at bonds and convert that to other forms of income that are currently better positioned, and try to identify the areas better positioned for growth in the future as well and keep in mind how down years of stock and bonds may see positive results in gold and commodities and how certain assets compliment each other. Or you can use some mixture of a more balanced strategy that allocates among a few asset classes evenly and this mixed with some tweaking based upon your outlook and adding cash as necessary or leveraging as necessary to better meet your goals and risk tolerance.

This is designed to get you thinking about how capital flowing from one asset class to another plus past history vs future potntial and your own volatility tolerance to come up with a flexible strategy that works for you and isn’t overly complicated to follow.

Comments »