By David K. Randall and Edward Krudy

NEW YORK (Reuters) – Stock-picking once again matters on Wall Street.

After a year in which stocks moved in near-lockstep regardless of individual merit, the herd mentality is crumbling away.

The move away from a frenzied rush in and then back out of the market is a welcome sign for stressed-out fund managers and lay investors alike.

“If I think something looks cheap I’m more prepared to own it because I think that will matter. Before, I would throw up my hands and say, ‘So what? If it’s perceived as a higher risk asset then it’s going to crater with any nasty news out of Europe,'” said Art Steinmetz, chief investment officer at OppenheimerFunds in New York.

The change reaffirms the diversification strategies that underpin trillions of dollars worth of savings meant for college tuition and retirement. When just about everything is moving in the same direction, investors have fewer ways to cushion market swoons.

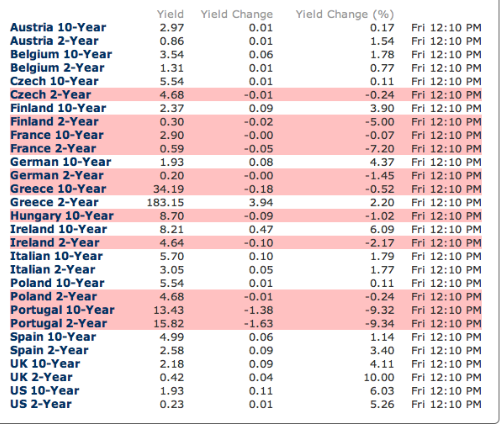

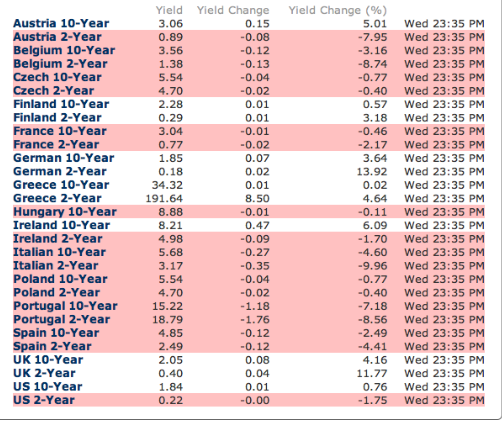

In 2011, daily activity in individual stocks was less dependent on company reports than on action in European government debt markets, and the equity, currency and commodities markets traded in tandem.

Now that stocks are going their own way, it’s been good for so-called active fund managers, those who decide what individual stocks are best to hold rather than follow an index.

In January, about 70 percent of active managers outperformed the S&P 500, compared with just 23 percent in 2011, according to Bank of America/Merrill Lynch data.

“Our traders have had their best month since 2009 because of the fall-off in correlation,” said Don Bright, a director and trader at Bright Trading in Chicago. “We’re doing a lot of homework on earnings since fundamentals are driving individual stocks again.”

Read the rest here.

Comments »