The fall in the headline consumer price index (CPI) in April for the second consecutive month has raised concern that the US economy might have fallen into a deflationary black hole. Year on year, the CPI fell by 0.7% in April after declining by 0.4% in the month before. For most experts, the emergence of deflation poses a serious threat to the economy. It is held that a fall in prices causes consumers to postpone their expenditure. Furthermore, deflation also raises real interest rates and the debt burden, thereby depressing further the overall demand for goods and services, so it is argued. After falling to negative 3.6% in July 2008, the real federal funds rate has been in an uptrend, climbing to positive 0.9% in April this year.

So how does one counter deflation? Some economists propose policies to promote a higher rate of inflation.

According to Harvard professors of economics Gregory Mankiw and Kenneth Rogoff, a higher rate of inflation will set the platform for a decline in real interest rates and for an increase in current consumer expenditure. Additionally a higher rate of inflation will work towards the reduction of the debt burden. This, they contend, will provide a necessary boost to economic activity.

So what is the level of inflation required to pull the economy from a deflationary black hole? Some experts, such as Rogoff, hold that 6 percent is the right figure:

I’m advocating 6 percent inflation for at least a couple of years. It would ameliorate the debt bomb and help us work through the deleveraging process.

So it seems that in the current economic setup a little bit of inflation is the correct remedy for the economy.

But how can something normally regarded as bad news — something that destroys the economy — at the same time promote economic health? Our Harvard professors don’t try to provide an answer to this question. All that matters for them is that a higher rate of inflation is going to revive consumer outlays, which they hold is going to strengthen the economy.

Are Increases in the Consumer Price Index What Inflation Is All About?

The main problem with this way of thinking is the definition of inflation. Most economists hold that inflation is a general rise in prices that can be captured by the consumer price index, but they disagree about the causes of inflation. In one camp are the monetarists, who argue that changes in money supply cause changes in the CPI. In the other camp, we have economists who argue that inflation is caused by various real factors. These economists have doubts about the proposition that changes in money supply cause changes in the CPI. They believe that it is likely to be the other way around.

We suggest that inflation is not rises in prices as such but the debasement of money.

Historically, inflation originated when a ruler would force the citizens to give him all the gold coins under the pretext that a new gold coin was going to replace the old one. In the process, the king would falsify the content of the gold coins by mixing it with some other metal and return to the citizens diluted gold coins.

The ruler can now use the stolen gold and mint coins for his own use. What was now passing as a pure gold coin was in fact a diluted gold coin. The expansion in the diluted coins that masquerade as pure gold coins is what inflation is all about. As a result of inflation, the ruler could engage in an exchange of nothing for something. (He could now divert real resources to himself).

Under the gold standard, the technique of abusing the medium of the exchange became much more advanced through the issuance of paper money unbacked by gold. Inflation therefore means here an increase in the amount of paper receipts that are not backed by gold yet masquerade as true representatives of money proper, gold. Again, the holder of unbacked money engages in an exchange of nothing for something.

In the modern world, the money proper is no longer gold but rather paper money; hence inflation in this case is purely the increase in the stock of paper money. Please note: we don’t say that inflation is about general increases in prices. Also note that we don’t say that the increase in the money supply causes inflation. What we are saying is that inflation is the increase in the money supply.

Once it is realized that inflation is about increases in the money supply, it becomes clear why it is bad news. When money increases, there are always first recipients of money who can buy more goods and services at still unchanged prices. The second recipients of money also enjoy the new money. However, the successive recipients derive less benefit as prices of goods and services begin to rise.

So long as the prices of goods they sell are rising much faster than the prices of goods they buy, the successive recipients of new money still benefit. The sufferers are those individuals who get the new money last — or not at all. They find that the prices of goods they buy have increased while the prices of goods and services they offer have hardly moved. In other words, monetary growth or inflation causes a redistribution of wealth.

On closer inspection, we can also establish that monetary injections give rise to demand for goods and services, which is not supported by the production of goods and services, implying that monetary growth leads to an economic impoverishment of wealth generators. Furthermore, monetary inflation gives rise to the menace of the boom-bust economic cycle.

Once it is established that the subject matter of inflation is the expansion of the money stock, we can attempt to ascertain whether the use of inflation can help to revive the US economy.

Monetary Inflation and Prices

What is the price of a good? It is the amount of money asked per unit of a good. Observe that, without money, one cannot even begin to discuss what prices are. Yet most economists, while discussing prices, never even mention money.

For mainstream economists, an increase in economic activity is almost always seen as a trigger for a general rise in prices, which they erroneously label “inflation.” But why should an increase in the production of goods lead to a general increase in prices? If the money stock stays intact, then we will have a situation of less money per unit of a good — a fall in prices. This conclusion is not affected even if the so-called economy operates very close to “potential output” (another dubious term used by mainstream economists).

Another popular explanation for a general rise in prices is the increase in wages once the economy is close to the potential output. If the amount of money remains unchanged then it is not possible to raise all the prices of goods and wages. So again, the trigger for a general rise in prices has to be monetary expansion.

An increase in the price of a particular good means that more money is now paid for this good. Likewise, if for a given stock of goods an increase in the money supply occurs, all other things being equal, this would mean that more money is going to be exchanged for the unit of this stock of goods. This means that the price of a good has now gone up.

Observe that in this case the increase in money supply (i.e., inflation) is associated with the increase in the prices of goods. (We have seen that most economists and commentators define inflation as a general rise in prices, which is summarized by the so-called consumer price index. Note again that, while a general rise in prices may be associated with inflation, it is however not inflation).

But now consider the following case: the rate of growth in money is in line with the rate of growth in goods. Consequently, there is no change in the prices of goods. Do we have inflation here or don’t we?

For most economists, if an increase in the money supply is exactly matched by the increase in the production of goods, then this is fine, since no increase in general prices has taken place and therefore no inflation has emerged. We suggest that this way of thinking is false since inflation has taken place, i.e., the money supply has increased. This increase cannot be undone by the corresponding increase in the production of goods and services.

For instance, once a king has created more diluted gold coins that masquerade as pure gold coins, he is able to exchange nothing for something irrespective of the rate of growth of the production of goods. Regardless of what the production of goods is doing, the king is now engaging in an exchange of nothing for something, i.e., diverting resources to himself by paying nothing in return.

The same logic can be applied to paper-money inflation. The exchange of nothing for something that the expansion of money sets in motion cannot be undone by the increase in the production of goods. The increase in money supply — i.e., the increase in inflation — is going to set in motion all the negative side effects that money printing does, including the menace of the boom-bust cycle, regardless of the increase in the production of goods.

Following our conclusion that inflation is about increases in money supply, it obviously cannot be beneficial for economic growth, as our Harvard professors have suggested. On the contrary, an increase in inflation results in the economic impoverishment, by diverting real wealth from wealth generators to the holders of newly printed money. It leads to consumption without supporting production.

Inflation and the Pool of Real Savings

Is it true that inflation helps to alleviate the debt burden in the economy? What raises the debt burden is the declining ability of individuals to create real wealth. Obviously, then, more inflation weakens the ability to create real wealth and can only increase and not reduce the debt burden.

Printing money can only temporarily help the first receivers of newly printed money. It cannot, however, help all the individuals in the economy. We can thus conclude that inflation can only raise and not lower the overall debt burden in the economy.

That inflation is a destructive process cannot always be seen when the underlying bottom line of the economy is still ok. For instance, when authorities are increasing the money-supply rate of growth while the pool of real savings is still in good shape, economic activity follows suit.

It is easy then to conclude that inflation and economic growth are moving in tandem. Once, however, the pool of real savings is in trouble, no monetary pumping can revive economic activity. (Remember, every activity, whether of wealth or non-wealth-generating nature, must be funded. Funding cannot be replaced with printing more money, i.e., more inflation. Funding is about real savings).

On the contrary, an increase in the rate of inflation, as recommended by our Harvard professors, further weakens the process of real savings formation — the key for economic growth. Good examples in this regard are the Great Depression of 1930s and Japanese depression of 1990s.

The importance of correct definition of inflation cannot be emphasized enough. Failing to identify, i.e., define inflation can produce nasty surprises. For instance, for most experts the key for a healthy economy is price stability. If general rises in prices follow a stable growth path economists are of the view that this points to a stable economic growth.

Now we have seen that while increases in money supply (i.e., inflation) are likely to be revealed in price increases as registered by the CPI, this need not always be the case. We have seen that prices are determined by real and monetary factors.

Consequently it can occur that if the real factors are pulling things in an opposite direction to monetary factors no visible change in prices might take place. In other words, while money growth is buoyant, i.e., inflation is high; prices might display low and stable increases.

Clearly, if we were to regard inflation as rises in the CPI, we would reach misleading conclusions regarding the state of the economy. (The increase in money supply regardless of the CPI rate of growth diverts real wealth from wealth generating activities to various non-productive activities thereby weakening the bottom line of an economy).

On this Rothbard wrote,

The fact that general prices were more or less stable during the 1920s told most economists that there was no inflationary threat, and therefore the events of the great depression caught them completely unaware. (America’s Great Depression, p. 153)

This means that the loose monetary policy of the Fed back then had significantly weakened the pool of real savings, notwithstanding the stable CPI. Hence analysts who ignore monetary pumping and only pay attention to changes in the CPI run the risk of overlooking what is really going on in the economy.

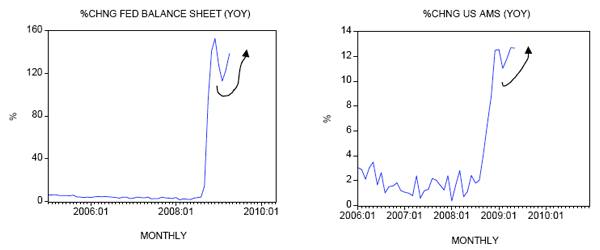

The whole idea that there is the need for more inflation in order to revive the economy seems preposterous given the fact that the Fed has been aggressively inflating since the end of last year. The yearly rate of growth of monetary pumping as depicted by the Fed’s balance sheet jumped from 3.8% in August last year to 152.8% by December 2008. At the end of April, the yearly rate of growth stood at 138.6%.

The growth momentum of our monetary measure, AMS, displays buoyancy. The yearly rate of growth of AMS jumped from 2% in August last year to 12.6% in May this year.