Public hatred for Martin Shkreli has unimaginable levels. Try to name a more disliked individual right now.

As a natural contrarian, I am jumping off the bandwagon and going long Martin Shrekli.

From Vanity Fair’s Bethany Mclean, “Everything You Know About Martin Shkreli Is Wrong – or Is It?

“I’m like Robin Hood,” he continues. “I’m taking Walmart’s money and doing research for diseases no one cares about.”

Of all the questions swirling around Shkreli, the strangest might be the most basic: How is it that a 32-year-old with no formal training in chemistry ended up running a pharmaceutical company?

In early 2000, when he was about to turn 17, he “weaseled” (his word) his way into an internship at Cramer Berkowitz, the hedge fund then run by CNBC financial pundit Jim Cramer.

He started in the mailroom but displayed a talent, right off the bat, for smoking out small biotech scams.

Shkreli got to know the small group of investors who focus on shorting such stocks—betting that they’ll go down when they prove ineffective or don’t get F.D.A. approval.

After four years, Shkreli left, and bounced around a few other firms before starting his own, Elea Capital Management.

In the summer of 2007, the fund tanked when Shkreli made a $2.6 million bet, through Lehman Brothers, that the market would decline. When he was wrong, he refused to pay Lehman, instead making “veiled threats of filing a bankruptcy,” according to a lawsuit. But it was Lehman which went down in flames, during the 2008 meltdown, and although the court found in its favor, the verdict was vacated.

“I wasn’t successful with my first hedge fund,” Shkreli says today. “I shut it down and lived with my parents. It was a fall from, well, not grace, but a fall.”

Around 2008, Shkreli started a second hedge fund, MSMB, a name made from his initials and those of his business partner and childhood friend, Marek Biestek. They developed a reputation for shorting biotech companies and then using stock chat rooms and other aggressive tactics to savage them, to cause the stock to go down.

Shkreli wrote for one investment site, “Clinical data can be misleading, innocently biased, meaningless, manipulated and sometimes even downright doctored.”

An investor points out, “Shkreli had a really good knowledge of who was faking drug results and who was gaming the system.”

Hedge-fund manager Rex Dwyer, who invests in small companies, including some biotech firms, remembers being introduced to Shkreli at a conference. “He’s quirky,” Dwyer says. “He has a super-high I.Q. It must be 160 or 180. His brain just crunches on things and comes up with answers. I’d ask him a question and he’d stare at me and not say anything. It weirded me out, but I realized he’d just disappeared into his brain.”

In the spring of 2012, MSMB announced that it was investing $4 million in a new biotech company called Retrophin, and Shkreli said that he was going to wind down MSMB to devote all of his time to the new company.

Why, at 29, did he switch from running a hedge fund to running a pharmaceutical company?

“There wasn’t enough money in hedge funds,” he tells me. “You could say that that is the biggest dickhead answer ever. Like most things I say, this could sound really off-putting.”

Money doesn’t seem to be his only motive. He helped in developing a potential treatment for another life-threatening rare disease, called PKAN, which was awarded a patent and is now in clinical trials.

“He has a rare respect and value for the science,” says a doctor who has worked with him. When Robin Anderson, a friend of the Kulsrud family, whose three children suffer from PKAN, contacted Shkreli via Twitter about the drug, he wrote back in 20 minutes, offering to do whatever he could to help. And she says he has.

In late 2012, Shkreli took Retrophin public through what’s known as a “reverse merger,” in which you merge a new business into an existing publicly traded shell, thereby getting stock that you can sell to investors.

Such deals are so notoriously sleazy that the S.E.C. has issued a bulletin warning investors to stay away from them. But at the time speculative biotech stocks were so hot, and Shkreli was apparently so convincing and his ideas seemed so brilliant, that, in early 2013, he was able to raise $9 million.

And with that, Retrophin was off and running. Over the next two years, the company raised an additional $100 million from investors, which included Steve Cohen’s SAC Capital, the family of Fred Hassan (a former C.E.O. of the pharmaceutical giant Schering-Plough, with whom Shkreli had become friendly at a pharmaceutical conference), and Brent Saunders, the current C.E.O. of Allergan, the maker of Botox.

At least some of the investors wanted in based on the promise that Retrophin was going to develop new drugs for rare diseases, but the company started to buy existing drugs—including Thiola, which helps prevent a rare form of kidney stone—and hike the prices.

One person close to events says that both Hassan and Saunders sold their stakes when they began to feel Retrophin was moving away from developing its own drugs.

In the spring of 2014, Shkreli began posting bullish messages online about the company’s prospects, as Retrophin’s stock was soaring, from around $3 a share in early 2013 to almost $20.

On May 29, he tweeted, without explanation, that “this is one of the best days of my life!” The next day he sold almost $4.5 million worth of his own stock in the company. This infuriated investors who believed he was cashing out.

It didn’t come as much of a surprise when Retrophin announced after the close of the market on September 30, 2014, that Shkreli had been replaced by Stephen Aselage, an early Retrophin employee who had quit and then rejoined the company as C.O.O. in 2014.

Not to be deterred, Shkreli set up new offices by the weekend, an investor recalls. “He has a relentless determination not to let anything stop him,” this person says.

Shkreli named his new company Turing, after Alan Turing, the British mathematician who played a key role in cracking the Nazi Enigma-machine codes and who was persecuted for being gay.

Last August, Turing announced the $55 million acquisition of Daraprim from Impax Labs, and Shkreli claimed that the company had raised $90 million from both himself and other investors in equity and debt. It is one of the largest financing rounds in biotech history, and there are many investors who still believe in him. “He has spectacular insights about medicines and diseases,” says one such investor. “He can sift through thousands of potential opportunities and find the one others have missed.”

“[Certain investors] think he knows how to work the system,” says another, more skeptical former investor. You can’t separate Shkreli’s ability to raise money from the environment. We have been in the midst of a historic biotech bubble, and, as another investor says, “when the crescendo is peaking, people are looking for the boy genius, the person who gets it. Martin became that boy.” And there’s this: people who invested in Retrophin made a lot of money.

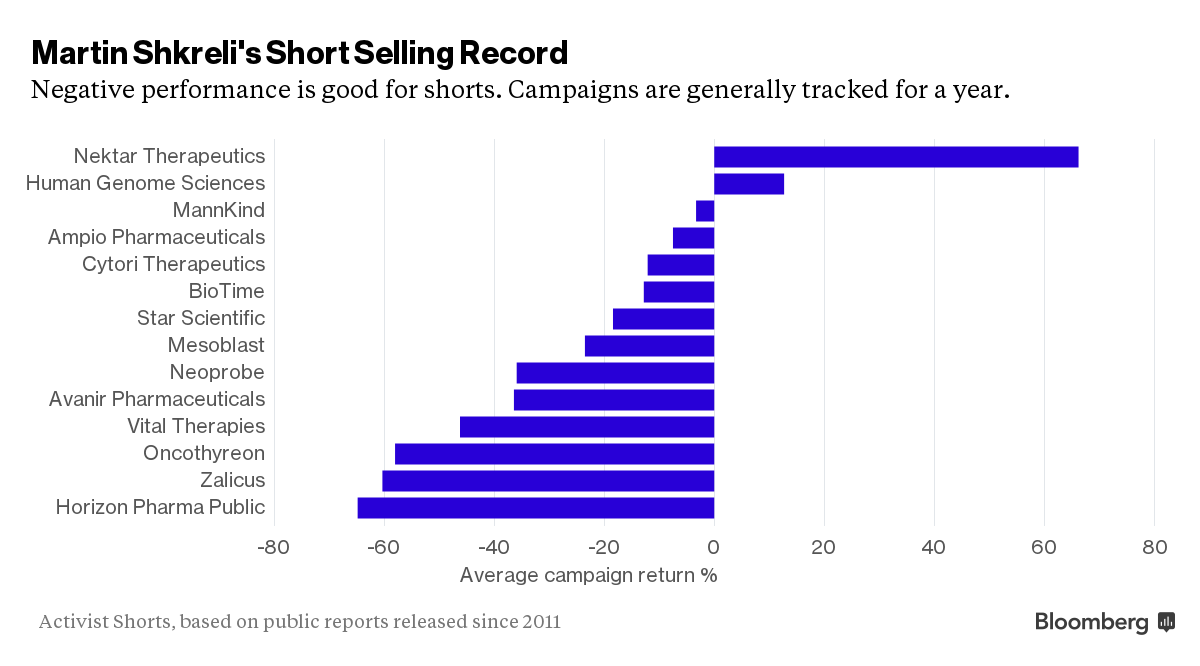

Despite getting blown out a couple times in the past. Shkreli’s more recent trading performance has been pretty impressive.

One ranking, by Activist Shorts puts the short bet performance of his published bearish calls above Citron, Tilson, Einhorn and Chanos.

In conclusion, Martin Shkreli should have been jailed years ago, but thanks to some luck, brilliance, and deception he beat the odds and kept the party going.

Investors are not suppose to make money in ponzi-schemes. Retrophin isn’t exactly a losing chart. Even those who got burned at his previous hedge fund were probably happy to have RTRX shares when it was trading at $35.

Hiking drug prices on drugs is morally objectionable. However, Shkreli is a small fry in the game. Many biotechs have outrageously priced drugs for rare-diseases, some costing over hundreds of thousands per patient, per year. These costly drugs benefit very few people worldwide (~10k), so to recoup R&D expenses, they justify their costs.

We need to decide if we want to live in a world where rare-diseases are a death sentence or curable, at a steep cost to the tax payer – Have fun with that debate.

GreedyPicks will become Shkreli’s oasis of solace, hidden amongst a vast desert of inter-web despise.

Don’t hate the player. Hate the game.

“Despite getting blown out a couple times in the past. Shkreli’s more recent trading performance has been pretty impressive.”

Um, no. MSMB also blew up and it was due to a short trade gone awry. Trading is not his game.

The game is politics and he blew it beyond any chance of recovery. The current charges are just the beginning.

He’s good at what he does. . .

Haters gunna hate