“Those of us who have attained a certain age can remember being bombarded by commercials in which we were asked “Is it live or is it Memorex?” The thrust of the ad was that it didn’t make any difference, that the tape recording was just as good as being there to watch that TV show live. Video recording technology was in its infancy, and the ability to play a movie whenever you wanted was really cool. Imagine being able to set a video recorder to record a TV show while you were away! … As long as you had somebody in the house young enough to be able to program the recorder to do it, it was great technology.

Today investors are asking themselves a similar question: “Is the meltdown in the stock market the result of Fed tapering, or is there something else going on?” We’ll address that question today and take a deep plunge into the emerging markets. We have a good old-fashioned central banker throwdown in progress, and if the results didn’t have such an impact on our investment portfolios, it could actually be quite fun to watch. What happens in the emerging markets will unfortunately not stay in the emerging markets. It’s all connected. There is more happening here than a simple correction. Let’s put our thinking caps on and try to connect some dots.

The current emerging-market meltdown is what Jonathan Tepper and I discussed in our book Endgame and specifically predicted in our latest book,Code Red. Let’s rewind the Memorex tape and see what we said:

This unprecedented global monetary experiment has only just begun, and every central bank is trying to get in on the act. It is a monetary arms race, and no one wants to be left behind. The Bank of England has devalued the pound to improve exports by allowing creeping inflation and keeping interest rates at zero. The Federal Reserve has tried to weaken the dollar in order to boost manufacturing and exports. The Bank of Japan, not to be outdone, is now trying to radically depreciate the yen. By weakening their currencies, these central banks hope to boost their countries’ exports and get a leg up on their competitors. In the race to debase currencies, no one wins. But lots of people lose.

Emerging-market countries like Brazil, Russia, Malaysia, and Indonesia will not sit idly by while the developed central banks of the world weaken their currencies. They too are fighting to keep their currencies from appreciating. They are imposing taxes on investments and savings in their currencies. All countries are inherently protectionist if pushed too far. The battles have only begun in what promises to be an enormous, ugly currency war. If the currency wars of the 1930s and 1970s are any guide, we will see knife fights ahead. Governments will fight dirty, they will impose tariffs and restrictions and capital controls. It is already happening, and we will see a lot more of it….

We are already seeing the unintended consequences of this Great Monetary Experiment. Many emerging-market stock markets have skyrocketed. Only to fall back to earth at the mere hint of any end to Code Red policies.

Emerging-market countries have to fend for themselves. Bernanke, Kuroda, and other developed-country central bankers accept no responsibility. If other countries don’t like a weaker dollar or yen, too bad. Bernanke places the blame, not on the United States for weakening the dollar, but on emerging countries for not revaluing their currencies or imposing capital controls. As U.S. Treasury Secretary John Connally said to foreign finance ministers in 1971, “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.” Indeed.

Let’s stop there for a moment, as this is an extremely important point. There have been numerous speeches by developed-world central bankers explicitly explaining that they are responsible for their own markets and that the central bankers of developing economies have to adjust on their own. Just as there have been many emerging-market central bankers complaining about quantitative easing in the developed world creating problems in their markets. In a few pages, we are going to look at a very important interview on Bloomberg with Raghuram Rajan, the brilliant head of the Reserve Bank of India, but now, back to Code Red:

Whenever the Fed hikes rates, bad things happen somewhere. It’s that simple. In 1994 the quick rise in rates killed a lot of leveraged investors in the bond market. Orange County had interest-rate derivatives that blew up in its face. It was the largest municipal bankruptcy in history. Emerging-market stocks and bonds were hammered, and Mexico was even forced to devalue its currency in a major financial market crisis. If (when) the Fed hikes rates today, we’ll see lots of bankruptcies like Orange County’s and blow-ups like the Mexican Tequila Crisis. The very low rates globally in a Code Red world mean that now there are probably hundreds or thousands of investors like Orange County. You can bet on that. And that is why the market gets so nervous about suggestions that the Fed might start tapering its quantitative easing. If QE is finally ended, can rising rates be far behind? [Or at least that’s the thinking!]

Recently, much of QE’s effects have been felt in emerging-market countries. This is a response not just from the U.S. Fed but from the BOJ, ECB, and BoE. Unlike the sick, indebted developed world, many emerging-market countries are growing and doing well. [Let me remind you that we wrote this in August 2013!] We have not seen a lot of borrowing in the developed markets. Instead, growth of credit and lending to private borrowers is happening in emerging markets. Emerging markets have been a popular target of excess capital for a number of reasons: their overall ability to take on debt remains strong, and their balance sheets are still relatively healthy; and more importantly, investment yields have been high relative to sovereign competitors. This two-speed world presents enormous problems. Code Red-type policies in the developed world are leading savers and investors to flee very low rates of return at home in favor of putting money into Turkey, Brazil, Indonesia or anywhere that offers higher rates of return.

Code Red-type monetary policies are designed to produce investment and growth, and they are! Just not in the countries that central banks intended to help. This is a major headache for governments in these countries. For them it is like having loads of visitors drop by all of a sudden. It is flattering that they like your house; but after a while, you’d rather they didn’t show up unexpectedly. Hot money flows are like drunken guests. They create a very big party, they leave unexpectedly, and they leave a god-awful mess behind. Large hot money flows have been behind most major emerging-market booms and busts.

Whenever major, developed-world central banks keep rates at very low levels and weaken their currencies, they cause bubbles. Let’s look at two recent bubbles and crashes that Code Red policies helped cause.

After the Japanese bubble burst in 1989, the bank of Japan cut interest rates close to zero. By 1995 the dollar/yen exchange rate weakened, and the yen lost almost half of its value. The Japanese took money out of Japan and put it into Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand. Investors in other countries borrowed money either directly in yen or through synthetic instruments. It was called the yen carry trade, and it was designed to take advantage of easy Japanese money to invest elsewhere. Everyone assumed that the yen would continue to go down, making the terms of repayment easier.

Asia attracted nearly half of the total capital inflow to emerging markets, and the stock markets of South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia were soaring. The party didn’t last forever. When the Thai currency came under pressure in June 1997, almost all Asian countries faced stock market crashes, capital flight, currency depreciations, and banking busts. The entire Asian episode perfectly fit the five stages of a bubble, but it was certainly much greater than it otherwise would have been, given the policies of the Bank of Japan….

The idea that ultra-low interest rates cause booms and busts is not new. Economists of the Austrian school, led by von Mises and Hayek, warned that credit-fueled expansions lead to the misallocation of real resources that end in crisis. In the Austrian theory of the business cycle, the central cause of a credit boom is the fall of the market rate of interest below the natural rate of interest. Investments that would not be profitable at higher rates become possible. The bigger the deviation of interest rates from the natural rate, the bigger the potential credit boom and the bigger the bust.

Like all bubbles, rapid price increases can rapidly reverse when interest rates return to normal levels. The greatest danger will then be to leveraged investors who bought farmland, corporate bonds, some emerging markets, and other bubbles with borrowed money.

Narrative or Reality?

The US Federal Reserve has begun to taper by $10 billion a meeting. That means they are still putting $65 billion a month into the world economy. Let’s do a thought experiment. If the Fed had originally announced they were going to do $65 billion per month in QE rather than the $85 billion they did announce, would it have made any difference in the overall outcomes? I would suggest there is not a great deal of actual difference between $85 billion and $65 billion. Yet now the markets are acting as if there is some massive difference.

I would submit to you that the difference is actually in the narrative. The Federal Reserve is signaling that it is going to end quantitative easing at some point in the future; therefore, investors are trying to find the exits before the end actually comes. But does it make any real difference to your portfolio whether it’s the reality or the narrative that is driving the volatility in the markets?

Sidebar: the US just printed 3.2% (annualized) GDP growth for the fourth quarter – a quarter in which the government was a significant drag. Without that drag, growth might have been 4%. In such an environment it is going to be difficult if not impossible for the Federal Reserve to discontinue the tapering of QE. If there is a surprise – and with continued growth there might be – it will be to increase the amount of easing each meeting. Just saying…

What’s Driving Emerging Markets?

The trouble in emerging markets is just beginning.

Hot money has been chasing a growth story across the emerging markets since early 2009. Trouble is, the real driver of economic growth in emerging markets is not the explosive force of eager, low-skilled workers as they climb into the middle class. That’s just the story you hear from mutual fund salesmen. That’s like saying the economy grows over time because we all get raises and spend the new income on plasma screen TVs.

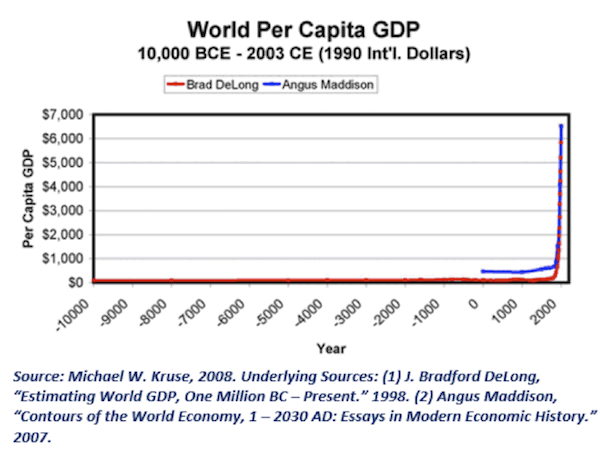

Emerging-market consumption is a RESULT of growing incomes, not the CAUSE. The real driver of long-term global growth has been the great spurts of innovation enabled by the last two industrial revolutions.

Longtime readers know I disagree with Professor Robert Gordon on his long-term forecasts for productivity growth. He specializes in economic history and is one of the finest productivity economists in the world, while I am just an amateur futurist with a wild imagination, but…

Dr. Gordon was absolutely right to proclaim the end of the Second Industrial Age. It began to pass away in the 1970s, and except for the boost from the 1980s through the early 2000s due to the advent of personal computers, the world economy has essentially been running on the fumes of a dying growth model, an unprecedented but now-deflating credit bubble, and the last high-spending years of wealthy but aging populations in the developed world.

As he attempts to peer beyond the chaos of debt, deleveraging, bankrupt governments, and desperate central banks that will ensue for the next five to ten years, Dr. Gordon’s dark and dire predictions about long-term growth hinge around the fact that he can’t see the rapidly accelerating technological transformation that promises to drive another century of explosive innovation. He doesn’t think it can happen again.

Can you blame him?

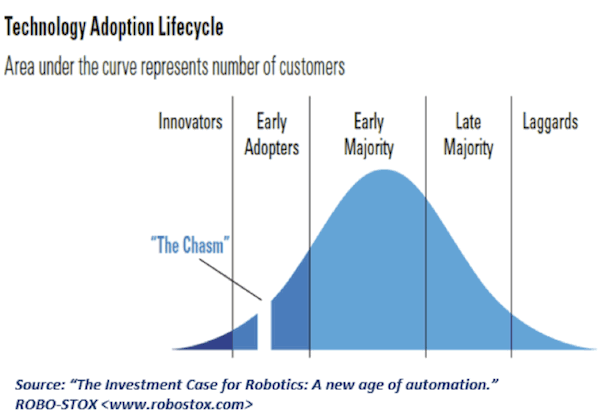

Identifying the next set of world-changing technologies before it “crosses the chasm” is infinitely harder than calling a market peak or a rare turn in the long-term credit cycle. In all of human history, we have seen only TWO sets of world-changing technologies that enabled centuries of follow-on innovation, inspired dynamic new industries, and revved up the faltering growth engines of ages past.

You would have to be extremely close to potentially world-changing technology to notice when it first leaps across the chasm, goes parabolic, and begins to drive a fresh explosion of innovation, productivity, and then – and only then – income.

But as you already know, the constant doubling of computing power since the late 1950s (known as Moore’s Law) has reached a point where our technological capabilities are taking exponentially larger leaps every year. And that constantly accelerating computing power is already enabling a massive round of follow-up innovation so disruptive that it looks and feels like magic.

That is great news for the human experiment and great news for the privileged minority in developing countries … but it could be terrible news for the vast majority of people in emerging markets who do not have the skills to participate in this new economy.

Contrary to popular belief, the real drivers of economic growth in most emerging markets are still investment and/or trade demand from the developed world. And those growth models – (A) attracting investment from the rich world to encourage development, (B) producing the things consumers in rich countries want, and/or (C) supplying the things manufacturing economies need to produce the things rich consumers want – are either running out of steam or becoming a lot more hazardous.

Let’s look at the longer-term challenge for export-oriented growth models first and then shift our attention to the sharp, Fed-induced reversal in capital flows that could devastate emerging economies in the coming months.

Emerging markets can’t depend on trade demand from the developed world…..”

If you enjoy the content at iBankCoin, please follow us on Twitter